i'm surprised, and impressed, by Kevin Smith. Clerks is the only film of his i've retained any fondness for, and as much as i'd written him off in recent years, he' s really done an admirable job of following it up. if the original helped redefine "indie film" as the medium quickly democratized, the second one is in many respects a good example of what Indie Film has become, for better or worse, twelve years later: a quiet, emotionally intelligent ensemble piece. (albeit that very special sort of ensemble piece that climaxes with man-on-donkey action.) Smith still doesn't have quite enough good taste to plug every sentimental or self-indulgent leak in his script, but he shows a remarkable flair for drama in several scenes, and Clerks II seems a lot more comfortable with itself than his previous work, particularly compared to the original's offputting (but endearing) staccato. and though the obscenity-as-comedy bit has worn thin over the years, Smith's casual, conversational (if sometimes overwrought) writing trusts his actors to elevate the material, and here it pays off more often than not. Smith himself would probably admit to being a bit of a hack, but twelve years after his debut he's come as close as ever to matching it, and made his most winning film to date.

i'm surprised, and impressed, by Kevin Smith. Clerks is the only film of his i've retained any fondness for, and as much as i'd written him off in recent years, he' s really done an admirable job of following it up. if the original helped redefine "indie film" as the medium quickly democratized, the second one is in many respects a good example of what Indie Film has become, for better or worse, twelve years later: a quiet, emotionally intelligent ensemble piece. (albeit that very special sort of ensemble piece that climaxes with man-on-donkey action.) Smith still doesn't have quite enough good taste to plug every sentimental or self-indulgent leak in his script, but he shows a remarkable flair for drama in several scenes, and Clerks II seems a lot more comfortable with itself than his previous work, particularly compared to the original's offputting (but endearing) staccato. and though the obscenity-as-comedy bit has worn thin over the years, Smith's casual, conversational (if sometimes overwrought) writing trusts his actors to elevate the material, and here it pays off more often than not. Smith himself would probably admit to being a bit of a hack, but twelve years after his debut he's come as close as ever to matching it, and made his most winning film to date.

Saturday, April 28, 2007

kevin smith's CLERKS II (2006)

i'm surprised, and impressed, by Kevin Smith. Clerks is the only film of his i've retained any fondness for, and as much as i'd written him off in recent years, he' s really done an admirable job of following it up. if the original helped redefine "indie film" as the medium quickly democratized, the second one is in many respects a good example of what Indie Film has become, for better or worse, twelve years later: a quiet, emotionally intelligent ensemble piece. (albeit that very special sort of ensemble piece that climaxes with man-on-donkey action.) Smith still doesn't have quite enough good taste to plug every sentimental or self-indulgent leak in his script, but he shows a remarkable flair for drama in several scenes, and Clerks II seems a lot more comfortable with itself than his previous work, particularly compared to the original's offputting (but endearing) staccato. and though the obscenity-as-comedy bit has worn thin over the years, Smith's casual, conversational (if sometimes overwrought) writing trusts his actors to elevate the material, and here it pays off more often than not. Smith himself would probably admit to being a bit of a hack, but twelve years after his debut he's come as close as ever to matching it, and made his most winning film to date.

i'm surprised, and impressed, by Kevin Smith. Clerks is the only film of his i've retained any fondness for, and as much as i'd written him off in recent years, he' s really done an admirable job of following it up. if the original helped redefine "indie film" as the medium quickly democratized, the second one is in many respects a good example of what Indie Film has become, for better or worse, twelve years later: a quiet, emotionally intelligent ensemble piece. (albeit that very special sort of ensemble piece that climaxes with man-on-donkey action.) Smith still doesn't have quite enough good taste to plug every sentimental or self-indulgent leak in his script, but he shows a remarkable flair for drama in several scenes, and Clerks II seems a lot more comfortable with itself than his previous work, particularly compared to the original's offputting (but endearing) staccato. and though the obscenity-as-comedy bit has worn thin over the years, Smith's casual, conversational (if sometimes overwrought) writing trusts his actors to elevate the material, and here it pays off more often than not. Smith himself would probably admit to being a bit of a hack, but twelve years after his debut he's come as close as ever to matching it, and made his most winning film to date.

Friday, April 27, 2007

ken loach's THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY (2006)

the world could use more artists like Ken Loach. over the past forty years, the iconoclastic British director has produced seventeen feature films and countless works for television, each of them brimming with the distinctly activist social conscience that’s seen him pegged as an unpatriotic agitator and kept more than a few projects off of the BBC’s airwaves. he’s also steadfastly resisted Hollywood’s beckon as it snatched up contemporaries and collaborators, and for good reason: his films seek to engage and enlighten rather than entertain.

the world could use more artists like Ken Loach. over the past forty years, the iconoclastic British director has produced seventeen feature films and countless works for television, each of them brimming with the distinctly activist social conscience that’s seen him pegged as an unpatriotic agitator and kept more than a few projects off of the BBC’s airwaves. he’s also steadfastly resisted Hollywood’s beckon as it snatched up contemporaries and collaborators, and for good reason: his films seek to engage and enlighten rather than entertain.thankfully, though, his talents have always struck a balance with his convictions, and as such adventurous, patient film fans have found much to love in his dramatic social realism. this is certainly the case with his most recent film, the Palm d’Or-winning The Wind That Shakes the Barley (as yet unreleased in Knoxville but currently available On Demand from Comcast), which sees Loach returning to history’s battlefields for a rich examination of the social economics of war and peace. set in early 1920s Ireland, Wind follows would-be medical student Damien O’Donovan (Cillian Murphy) as the brutality of British occupational forces spurs him to forego his studies and join his brother Teddy (Padraic Delaney) in the Irish Republican Army.

the two fight alongside each other for their cause, but a new conflict begins to arise from within even before the eventual military truce: Damien sees Ireland’s need for not only sovereignty but also a fresh socioeconomic start, while Teddy’s approach to expelling the Black And Tans is pragmatic and shortsighted, focusing only on tangible, immediate victory. when Ireland and Britain finally do sign a treaty ending the struggle (leaving Northern Ireland under British rule and the remaining Irish Free State conspicuously under the royal thumb), Teddy becomes an officer in the Irish government while Damien joins a growing coalition discontent with simply changing “the accents of the powerful and color of the flag.” The resulting Irish Civil War thus sets forth the perennial tragedy of brother against brother on the battlefield.

this isn’t unfamiliar territory for Loach, who probed similar ideological disconnect in the trenches of the Spanish Civil War in 1995’s Land and Freedom. but where that film followed a group of British volunteers into an increasingly hopeless foreign conflict, Wind strikes a far more personal tone as the O’Donovans see nationalism and familial love irrevocably clash, and this emotionally intimate angle on the politics of revolution is well-served by Loach’s typically naturalistic approach. the largely inexperienced Irish cast infuses the film with a passion rooted in the cultural repercussions of the Civil War that continue to haunt their country generations later, and though the O’Donovan brothers are certainly the center of the story, the script continually allows for an ensemble approach that pushes the historical and psychological detail to immersive levels.

the one drawback to Loach’s socialist fervor, however, is that he’s distinctly uninterested in presenting any viewpoint besides his own, and as a result the film sometimes feels like more of an ethics lecture than a history lesson. though by all accounts the Black And Tans were certainly ruthless, Wind presents them as caricatures of pure barbarity, drawing a thick black line between Good (the Irish) and Evil (the Britons). and while this low-key propagandizing certainly isn’t fatal, it does set up a problem for the final act: once the film’s sympathies shift to Damien’s side of the Civil War, Teddy’s initially lionized character is muddled by Loach’s continued inability to separate his cause from his content, and as a result the final scenes are robbed of the resonance they deserve.

otherwise, The Wind That Shakes the Barley is a remarkably nuanced, poignant essay on military occupation and the cultural and economic implications of rebuilding a nation in the face of continued war. it champions humanism and basic welfare as the building blocks of healthy nations, and laments that the horror of what we fight against can overshadow the intricacies of what we’re fighting for. and while it’s a shame that Ken Loach continues to blind his work to conflicting ideas, it’s some consolation that, forty years into his career, he’s still able to express his own with such eloquence.

(from the KNOXVILLE VOICE)

Thursday, April 26, 2007

williams street's AQUA TEEN HUNGER FORCE COLON MOVIE FILM FOR THEATERS (2007)

though it can be self-indulgent and overly juvenile, ATHF is honestly a pretty brilliant show, standing on the shoulders of Space Ghost Coast To Coast's sublime, revolutionary absurdity and somehow taking it a step further in both popularity and sheer strangeness, if not quality. but it can also be exhausting, and even in fifteen-minute installments it constantly verges on narrative implosion, so it was a pleasant enough surprise that Colon Movie Film For Theaters afforded itself a fair bit of breathing room without losing too much of its verve. as with the Reno 911 movie, it would have been interesting for the show to step out of its comfort zone a little, but there's also something to be said for sticking with what works, and for an epic, stoned non sequitur it works pretty well at feature length.

though it can be self-indulgent and overly juvenile, ATHF is honestly a pretty brilliant show, standing on the shoulders of Space Ghost Coast To Coast's sublime, revolutionary absurdity and somehow taking it a step further in both popularity and sheer strangeness, if not quality. but it can also be exhausting, and even in fifteen-minute installments it constantly verges on narrative implosion, so it was a pleasant enough surprise that Colon Movie Film For Theaters afforded itself a fair bit of breathing room without losing too much of its verve. as with the Reno 911 movie, it would have been interesting for the show to step out of its comfort zone a little, but there's also something to be said for sticking with what works, and for an epic, stoned non sequitur it works pretty well at feature length.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

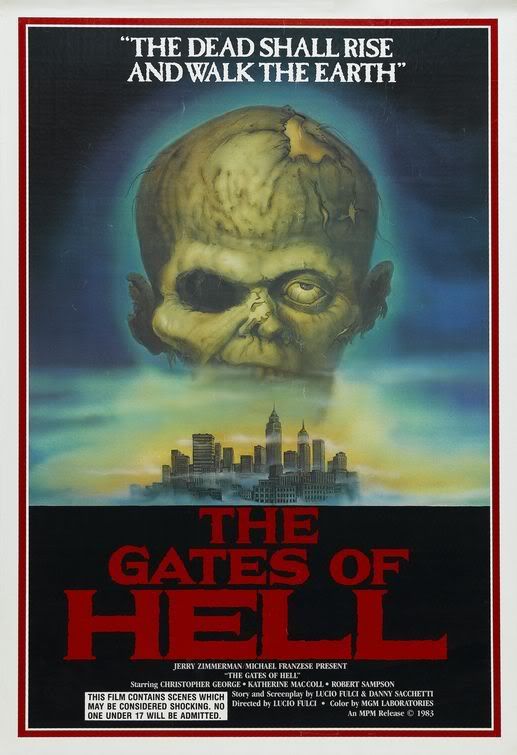

lucio fulci's CITY OF THE DEAD (1980)

i'm a little out of my element here with italian zombie scuzz, but i can say that Fulci's ability to wrench mood and atmosphere from poor performances and sub-modest production values really impresses. (if my limited recollection of Zombi serves me, that seems to be his typical aesthetic, but it still suggests a vision strong enough to overcome such shortcomings.) the music is great (until the end at least) and the gore is positively stomach-turning, especially in the notorious gut-vomit scene. but it all sputters to a slow stop during the (anti-)climax, and then nails the coffin shut with an unintelligible, unintentionally silly ending. sad that something with such ideas, such promise, could be so flawed.

i'm a little out of my element here with italian zombie scuzz, but i can say that Fulci's ability to wrench mood and atmosphere from poor performances and sub-modest production values really impresses. (if my limited recollection of Zombi serves me, that seems to be his typical aesthetic, but it still suggests a vision strong enough to overcome such shortcomings.) the music is great (until the end at least) and the gore is positively stomach-turning, especially in the notorious gut-vomit scene. but it all sputters to a slow stop during the (anti-)climax, and then nails the coffin shut with an unintelligible, unintentionally silly ending. sad that something with such ideas, such promise, could be so flawed.

Saturday, April 21, 2007

edgar wright's HOT FUZZ (2007)

parody has always been satire’s ne’er-do-well stepbrother, but the cinema of recent years has been particularly unkind to it, with Scary Movie and its ilk actively devolving the genre into strings of crass jokes and shallow pop culture references swept from the floor of an unfruitful Cracked Magazine writer’s meeting. so exhilarating, then, that Hot Fuzz sees Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg deliver on the promise of their “zom-rom-com” Shaun Of The Dead, thoughtfully turning their eye to contemporary action film with affection, respect, and no small amount of wit. it’s Wright’s grip on the grammar of the Big-Ass Action Flick that really sells it; Hot Fuzz’s quiet first act, for instance, is occasionally punctuated by rapid, showy montage that, recontextualized into the mundane, highlights an inherent obnoxiousness, while the film’s action-packed climax cribs directly (and effectively) from the Michael Bay / Tony Scott playbook with playful awe.

parody has always been satire’s ne’er-do-well stepbrother, but the cinema of recent years has been particularly unkind to it, with Scary Movie and its ilk actively devolving the genre into strings of crass jokes and shallow pop culture references swept from the floor of an unfruitful Cracked Magazine writer’s meeting. so exhilarating, then, that Hot Fuzz sees Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg deliver on the promise of their “zom-rom-com” Shaun Of The Dead, thoughtfully turning their eye to contemporary action film with affection, respect, and no small amount of wit. it’s Wright’s grip on the grammar of the Big-Ass Action Flick that really sells it; Hot Fuzz’s quiet first act, for instance, is occasionally punctuated by rapid, showy montage that, recontextualized into the mundane, highlights an inherent obnoxiousness, while the film’s action-packed climax cribs directly (and effectively) from the Michael Bay / Tony Scott playbook with playful awe.as impressive as the artifice is, though, the film obviously couldn’t rely on stylistic quotation alone. thankfully Fuzz’s script is full of both the low-key, character-driven comedy and clever command of genre that made Shaun Of The Dead such a joy, and the way the three elements work together reveals a lot about the nature of accomplished parody. the film has its own story to tell, and weaves genre convention (subverted, exalted, or both) together with genuine comedy where lesser efforts would simply rely on one to prop up the other. the result, then, is maybe less a parody than a riotously funny, only slightly backhanded homage.

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

alfred hitchcock's NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1959)

The most interesting thing about North By Northwest as compared to Hitchcock’s other best-regarded thrillers is that it’s flippant, even silly; you can almost hear Hitch chuckling in the background of every scene. Part of this is naturally due to Cary Grant’s signature gentle self-parody, but both Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman are perfectly willing accomplices, allowing/encouraging Grant to defuse their expert suspense scenarios with outrageous aplomb. Megadosed with bourbon and put behind the wheel of a car, for instance, Grant’s Thornhill opts not to brake, but rather visibly settles in for a nice drunken drive, while later in the film an understated auction scene, rife with tension, is gleefully torpedoed (and cleverly resolved) with absurd outbursts and sucker punches. But despite Grant’s general goofiness and Eva Marie Saint’s censor-needling innuendoes, it’s Hitchcock that drolly steals show, thanks to the middle-of-nowhere duel between Grant and a rogue crop-duster; this implausible, leftfield plot detour has its company among his most iconic sequences, but as a synthesis of his stylistic virtuosity and formidable wit, it’s practically peerless. overall NxNW is a touch sloppier than his other major works, mostly due to the consistent stutter of its pacing (climaxing in a final narrative hiccup that never fails to disappoint) and an admitted overabundance of levity, but there's highlight reel moments a-plenty, and for what it's worth it's one of his broadest entertainments.

The most interesting thing about North By Northwest as compared to Hitchcock’s other best-regarded thrillers is that it’s flippant, even silly; you can almost hear Hitch chuckling in the background of every scene. Part of this is naturally due to Cary Grant’s signature gentle self-parody, but both Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman are perfectly willing accomplices, allowing/encouraging Grant to defuse their expert suspense scenarios with outrageous aplomb. Megadosed with bourbon and put behind the wheel of a car, for instance, Grant’s Thornhill opts not to brake, but rather visibly settles in for a nice drunken drive, while later in the film an understated auction scene, rife with tension, is gleefully torpedoed (and cleverly resolved) with absurd outbursts and sucker punches. But despite Grant’s general goofiness and Eva Marie Saint’s censor-needling innuendoes, it’s Hitchcock that drolly steals show, thanks to the middle-of-nowhere duel between Grant and a rogue crop-duster; this implausible, leftfield plot detour has its company among his most iconic sequences, but as a synthesis of his stylistic virtuosity and formidable wit, it’s practically peerless. overall NxNW is a touch sloppier than his other major works, mostly due to the consistent stutter of its pacing (climaxing in a final narrative hiccup that never fails to disappoint) and an admitted overabundance of levity, but there's highlight reel moments a-plenty, and for what it's worth it's one of his broadest entertainments.

Saturday, April 07, 2007

rodriguez & tarantino's GRINDHOUSE (2007)

it's difficult to approach Grindhouse from a critical point of view, at least so soon after a first viewing, because it still exists in my mind as an experience rather than a work of art. the film's publicity has made a whole lot of noise about Tarantino and Rodriguez's yearning affection for the bygone days of schlocksploitation double features, but in practice Grindhouse reaches more universal heights, even for those who know the film's reference points only by vague reputation: it reminds us how ridiculously fucking fun it can be to go out and see a movie. as the audience laughed, cheered, hooted, hollered, clapped and cursed in harmony with each other, there was a glow of shared experience that's all but foreign in latter-day cineplexes, and for the first time in a long time i felt like i'd really gotten my eight bucks' worth.

it's difficult to approach Grindhouse from a critical point of view, at least so soon after a first viewing, because it still exists in my mind as an experience rather than a work of art. the film's publicity has made a whole lot of noise about Tarantino and Rodriguez's yearning affection for the bygone days of schlocksploitation double features, but in practice Grindhouse reaches more universal heights, even for those who know the film's reference points only by vague reputation: it reminds us how ridiculously fucking fun it can be to go out and see a movie. as the audience laughed, cheered, hooted, hollered, clapped and cursed in harmony with each other, there was a glow of shared experience that's all but foreign in latter-day cineplexes, and for the first time in a long time i felt like i'd really gotten my eight bucks' worth.Rodriguez's segment seems the more successful of the two films, at least insofar as the project's thesis goes: Planet Terror grabs the bronco of grindhouse cinema by its horns and balls and manages to hang on for most of its running time, primarily thanks to a wealth of wit, energy and ideas that somehow keeps the novelty of the whole spectacle from wearing off. (oddly, when it does sadly and inevitably lose its momentum, the most direct culprit is Tarantino, in a terrible cameo role that could almost be interpreted as sabotage.) the final sequences remain interesting, though, and despite their mania amount to a sort of break for the audience, who upon its conclusion are immediately assaulted with a series of breathlessly brilliant Coming Attractions mockups by Rob Zombie, Edgar Wright and Eli Roth. (Roth's in particular is hilariously, uncomfortably spot-on in its evocation of the no-budget slash trash for which i harbor an extreme phobia.)

Tarantino's segment, however, proves to be a different animal. where Planet Terror is Robert Rodriguez's love letter to the films from which Grindhouse takes its inspiration, Death Proof is, as usual, Quentin Tarantino's love letter to Quentin Tarantino; the first of the film's two acts is fatally, self-indulgently bloated with his trademark Witty Banter, and for the second time over the course of Grindhouse's three-plus hour running time, Quentin Tarantino is responsible for bringing everything to a screeching halt. but we've all learned two things about Tarantino over the course of his career: 1) he's an insufferable douchebag and 2) it doesn't matter, because he's a genuinely brilliant filmmaker. accordingly, a sudden, shocking climax throws the unsettled audience into an unexpected second act that initially echoes the first act's inactivity but quickly begins to take its own shape, culminating in an extended action sequence as visceral and expert as anything in Tarantino's oeuvre. Death Proof's payoff not only retroactively transforms the first act's unconcerned pacing into a ballsy model of unconventional exposition, but also more impressively elevates the film as a whole into an amalgamated homage to exploitation cinema that reduces Planet Terror to mere mimicry by comparison.

overall, though, the expertly sequenced double feature format does both films favors that probably prove key to their individual successes, and the pacing and energy of Grindhouse as a whole makes it more than the sum of its parts. it's by some measure the most fun i can remember ever having at the movies, and i look forward to seeing it again.

Tuesday, April 03, 2007

robert altman's CALIFORNIA SPLIT (1974)

even shoulder to shoulder with the rest of Altman's filmography, California Split is astonishingly naturalistic; plot is generally of little use to it, and it offers instead a character study of the Gambler, as portrayed by George Seagal and Elliot Gould as two sides of the same coin, banding together in an effort to appease their sickness. Gould is magnetic as always, and the more compelling of the two, as the thrill of the wager seems to have become a Great Truth in the manner he lives his life, and in collaboration with Seagal he becomes the ultimate enabler. but their connection, however ugly in its realities, yields a certain passion between the two men, and so Split is also a softly touching examination of an adoring (but nonetheless star-crossed) platonic relationship.

even shoulder to shoulder with the rest of Altman's filmography, California Split is astonishingly naturalistic; plot is generally of little use to it, and it offers instead a character study of the Gambler, as portrayed by George Seagal and Elliot Gould as two sides of the same coin, banding together in an effort to appease their sickness. Gould is magnetic as always, and the more compelling of the two, as the thrill of the wager seems to have become a Great Truth in the manner he lives his life, and in collaboration with Seagal he becomes the ultimate enabler. but their connection, however ugly in its realities, yields a certain passion between the two men, and so Split is also a softly touching examination of an adoring (but nonetheless star-crossed) platonic relationship.

Monday, April 02, 2007

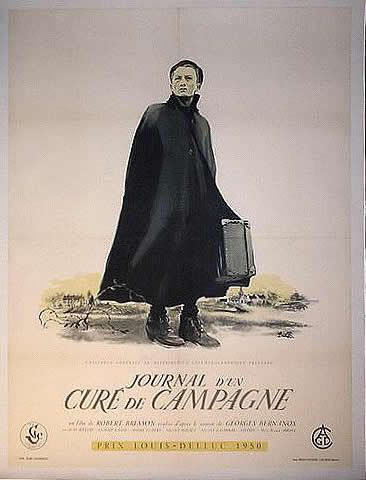

robert bresson's DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST (1951)

the thing that's most striking to me about Robert Bresson is that his craft is so internal - unschooled performances and an almost indifferent visual approach come together in his hands as distilled, otherworldly melodrama in touch with the human (or donkey) condition, so bleak and beautiful, while the mechanics remain obscured. sad that Country Priest was showing (at nashville's belcourt) a week too early for easter; it seems like it would be a pretty powerful way for adventurous christians to spend their holiest day. but it's sad, and it doesn't offer any easy answers. has god has abandoned the ambricourt parish? possibly. (it doesn't offer so much as an easy question.) but the priest is god's device of grace, and hope clings to the sorry creatures that surround him. the climax of the second act, wherein he rebuilds a grieving mother's faith by tearing her down, is drunk on equal parts Holy Spirit and stony fatalism, and is surely among the screen's most harrowing, insightful ruminations on the politics of faith. but the rest of the film is a minor key played softly, just as with Bresson's other work. his filmmaking doesn't insist upon itself, even as it clutches your lapel and leads a sad dance.

the thing that's most striking to me about Robert Bresson is that his craft is so internal - unschooled performances and an almost indifferent visual approach come together in his hands as distilled, otherworldly melodrama in touch with the human (or donkey) condition, so bleak and beautiful, while the mechanics remain obscured. sad that Country Priest was showing (at nashville's belcourt) a week too early for easter; it seems like it would be a pretty powerful way for adventurous christians to spend their holiest day. but it's sad, and it doesn't offer any easy answers. has god has abandoned the ambricourt parish? possibly. (it doesn't offer so much as an easy question.) but the priest is god's device of grace, and hope clings to the sorry creatures that surround him. the climax of the second act, wherein he rebuilds a grieving mother's faith by tearing her down, is drunk on equal parts Holy Spirit and stony fatalism, and is surely among the screen's most harrowing, insightful ruminations on the politics of faith. but the rest of the film is a minor key played softly, just as with Bresson's other work. his filmmaking doesn't insist upon itself, even as it clutches your lapel and leads a sad dance.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)