The rise of totalitarianism in Europe following the First World War has been an understandably central preoccupation in Western culture over the past century, and cinema, our youngest art, has proved among the most impressionable in its wake. From propaganda to popcorn flicks, the physical and psychological violence of our collective experience with—and within—oppressive states has resulted in countless films both important and entertaining, and this spectacle of a history filtered through celluloid has created and refined for us an iconography of good, evil, freedom and fear. We’ve been less receptive, however, to the notion of idealistic defeat, and thus those regimes (Franco, the Soviets) that survived the 1940s have, beyond a Cold War mentality rooted as much in nuclear paranoia as anti-Communism, been downplayed as they fell into slow decline toward the end of the century.

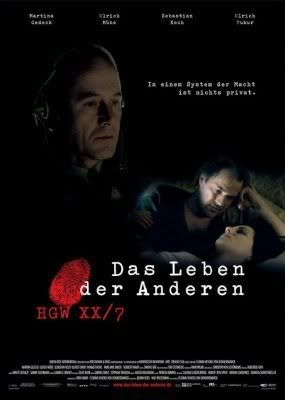

The rise of totalitarianism in Europe following the First World War has been an understandably central preoccupation in Western culture over the past century, and cinema, our youngest art, has proved among the most impressionable in its wake. From propaganda to popcorn flicks, the physical and psychological violence of our collective experience with—and within—oppressive states has resulted in countless films both important and entertaining, and this spectacle of a history filtered through celluloid has created and refined for us an iconography of good, evil, freedom and fear. We’ve been less receptive, however, to the notion of idealistic defeat, and thus those regimes (Franco, the Soviets) that survived the 1940s have, beyond a Cold War mentality rooted as much in nuclear paranoia as anti-Communism, been downplayed as they fell into slow decline toward the end of the century.It’s from this twilight that German director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck conjures his award-winning debut feature, The Lives Of Others (Das Leben der Anderen). His low-key approach to the material serves its setting well, drawing the slow crumble of East German communism into psychological focus through the story of a playwright, his muse, and the government agent assigned to eavesdrop on their every word. As it begins, Stasi captain Gerd Weisler (Ulrich Mühe), a ruthless interrogator and an academy instructor to secret-police cadets, is approached with an assignment undoubtedly common in 1980s East Berlin: overseeing the surveillance of a suspected subversive, writer Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch). Weisler dutifully accepts, and begins gathering tentative evidence of Dreyman’s reserved dissidence, but playing voyeur to the intellectual and emotional lives of Dreyman and his live-in girlfriend, Christa-Maria (Martina Gedeck), quickly yields unexpected results: Weisler’s own subdued, solitary existence, defined only by his role in a decaying regime, contrasts starkly with the intimacy and relative happiness of his charges, and so he is driven from fascination to envy, and from envy to empathy. He listens, rapt with attention at his attic desk, as Dreyman plays the piano, and Weisler even ventures into the apartment in their absence, examining a wooden salad fork, given as a birthday present, for the “beauty” with which Dreyman has described it.

Refreshingly, this obsession never delves into any of the boring perversity we’ve come to expect from such movies, but instead emerges as the moral and ethical crux of the film. (Though subplots concerning a coerced affair and an illicit manuscript occasionally tear the narrative away from Weisler, it’s very much his story.) As von Donnersmarck’s quiet thriller begins to close in on its characters, Weisler finds himself torn between his allegiance to his country and his own realizations about human nature and dignity; even as he is bound by duty to preside over one character’s eventual betrayal of another, the look in his otherwise cold eyes suggests that he, too, has been betrayed.

Weisler’s story is, of course, also the story of East Germany itself as it woke from a 40-year nightmare. Thankfully, von Donnersmarck approaches the material with a delicately humanist social realism that keeps the film from wallowing in its allegory. It’s not hard to imagine the characters drawn in broad strokes by less careful hands (archetype dictates Weisler as a tragic figure and Dreyman as a brave, brash reformer) but here both are suitably complex to sustain the film’s introspective tone, which makes its points without lecturing. The visual approach is similarly restrained, as the largely static frames take us back and forth between the warmth of Dreyman’s apartment and the shivering, empty streets and corridors of East Germany.

It’s this restraint, though, that ultimately prevents the film from being as engaging as it might like to be. Whether Weisler’s general quietude is his own true nature or just a by-product of his position, his character arc is often confoundingly introverted, and while we’re interested in Dreyman and Christa-Maria, the nature of the story holds us at arm’s length, and our concern remains solely intellectual. It doesn’t help that the two-hour-plus film is conspicuously stingy with its levity, nor that its epilogue, while stopping thankfully short of sentimentality, closes the film on a mildly unsatisfying note.

Despite these missed connections, The Lives Of Others has a lot to say about a painful period in Europe’s history largely unexamined on film, and first time writer/director von Donnersmarck makes an impressive, gently assured showing that’s earned awards the world over, most recently beating out multiple-nominee Pan’s Labyrinth for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. Although it lacks the bravura and brilliance of Pan’s superior Fascist fable, the two films share a message common and essential to all of the art that has helped us survive the last century, and all the centuries before that: humanity prevails.

(from the KNOXVILLE VOICE)

No comments:

Post a Comment