it's been a long time since a movie affected me quite so much as Little Children, and days later i still can't put my finger on why; the film as a whole is dour, uncomfortable and a little overwrought, focusing sometimes lazily (though always eloquently) on the same bourgeoise malaise done to death by inferior but more accessible films like American Beauty. on the other hand, though, Field and Perotta's emotional and psychological incisions fearlessly graze bone throughout, whether presenting a sad man resigned to his monstrousness (Jackie Earle Haley's scene in the parked car will bother me for the rest of my life) or a pair of adulterers wrestling poignantly with the situation they so carelessly careened into hopelessness and hurt. in a lot of ways Little Children recalls the work of Todd Solondz: it's self-consciously shocking, and even occasionally blase in its deviant provocation. but Solondz snickers at his characters, and at the audience squirming in their seats; Field, on the other hand, maintains an austerity even in rare moments of levity, and while Little Children may be a hard film to sit through, we aren't ever left to question what it's made us feel.

it's been a long time since a movie affected me quite so much as Little Children, and days later i still can't put my finger on why; the film as a whole is dour, uncomfortable and a little overwrought, focusing sometimes lazily (though always eloquently) on the same bourgeoise malaise done to death by inferior but more accessible films like American Beauty. on the other hand, though, Field and Perotta's emotional and psychological incisions fearlessly graze bone throughout, whether presenting a sad man resigned to his monstrousness (Jackie Earle Haley's scene in the parked car will bother me for the rest of my life) or a pair of adulterers wrestling poignantly with the situation they so carelessly careened into hopelessness and hurt. in a lot of ways Little Children recalls the work of Todd Solondz: it's self-consciously shocking, and even occasionally blase in its deviant provocation. but Solondz snickers at his characters, and at the audience squirming in their seats; Field, on the other hand, maintains an austerity even in rare moments of levity, and while Little Children may be a hard film to sit through, we aren't ever left to question what it's made us feel.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

todd field's LITTLE CHILDREN (2006)

it's been a long time since a movie affected me quite so much as Little Children, and days later i still can't put my finger on why; the film as a whole is dour, uncomfortable and a little overwrought, focusing sometimes lazily (though always eloquently) on the same bourgeoise malaise done to death by inferior but more accessible films like American Beauty. on the other hand, though, Field and Perotta's emotional and psychological incisions fearlessly graze bone throughout, whether presenting a sad man resigned to his monstrousness (Jackie Earle Haley's scene in the parked car will bother me for the rest of my life) or a pair of adulterers wrestling poignantly with the situation they so carelessly careened into hopelessness and hurt. in a lot of ways Little Children recalls the work of Todd Solondz: it's self-consciously shocking, and even occasionally blase in its deviant provocation. but Solondz snickers at his characters, and at the audience squirming in their seats; Field, on the other hand, maintains an austerity even in rare moments of levity, and while Little Children may be a hard film to sit through, we aren't ever left to question what it's made us feel.

it's been a long time since a movie affected me quite so much as Little Children, and days later i still can't put my finger on why; the film as a whole is dour, uncomfortable and a little overwrought, focusing sometimes lazily (though always eloquently) on the same bourgeoise malaise done to death by inferior but more accessible films like American Beauty. on the other hand, though, Field and Perotta's emotional and psychological incisions fearlessly graze bone throughout, whether presenting a sad man resigned to his monstrousness (Jackie Earle Haley's scene in the parked car will bother me for the rest of my life) or a pair of adulterers wrestling poignantly with the situation they so carelessly careened into hopelessness and hurt. in a lot of ways Little Children recalls the work of Todd Solondz: it's self-consciously shocking, and even occasionally blase in its deviant provocation. but Solondz snickers at his characters, and at the audience squirming in their seats; Field, on the other hand, maintains an austerity even in rare moments of levity, and while Little Children may be a hard film to sit through, we aren't ever left to question what it's made us feel.

taika cohen's EAGLE VS SHARK (2007)

it's not hard to see why the dry, perversely sweet Eagle Vs Shark elicited scads of Napoleon Dynamite comparisons: overdesigned, undercooked, and undeniably charming, both films half-mockingly celebrate social retardation where most prefab indies stop short at simple dysfunction. but in the end both films also fall victim to the same trap: like Napoleon and his clan, both Lily and Jarrod are far too affected and caricaturish to make an emotional connection with, or even really like; the most that can be said is that we only root for Lily to end up with the childish, unlikable Jarrod because it's clear he's probably the best she can do.

it's not hard to see why the dry, perversely sweet Eagle Vs Shark elicited scads of Napoleon Dynamite comparisons: overdesigned, undercooked, and undeniably charming, both films half-mockingly celebrate social retardation where most prefab indies stop short at simple dysfunction. but in the end both films also fall victim to the same trap: like Napoleon and his clan, both Lily and Jarrod are far too affected and caricaturish to make an emotional connection with, or even really like; the most that can be said is that we only root for Lily to end up with the childish, unlikable Jarrod because it's clear he's probably the best she can do.

re:

cohen,

comedy,

new zealand,

quirky

paddy breathnach's SHROOMS (2007)

part of me wouldn't have minded enjoying Shrooms; the premise isn't necessarily the worst that teen horror has to offer, and it's put together handsomely enough. but damned if it doesn't use its psychotropic premise as an excuse not to make any sense, and as such forgoes any real scares despite the odd tense moment. and more egregious than the nonsense is that the film gets so caught up in its boring, hackneyed twist that it almost entirely forgets to mislead beyond a bit of cursory j-horror aesthetic pilfering. we're misled into thinking there's a supernatural element to the proceedings, and its three manifestations could have been genuinely interesting and even (gasp!) scary in their dynamic interrelations, but despite their seeming high profile, the script never thinks to treat the supposed ghosts/monsters/whatevs as anything but a throwaway red herring.

part of me wouldn't have minded enjoying Shrooms; the premise isn't necessarily the worst that teen horror has to offer, and it's put together handsomely enough. but damned if it doesn't use its psychotropic premise as an excuse not to make any sense, and as such forgoes any real scares despite the odd tense moment. and more egregious than the nonsense is that the film gets so caught up in its boring, hackneyed twist that it almost entirely forgets to mislead beyond a bit of cursory j-horror aesthetic pilfering. we're misled into thinking there's a supernatural element to the proceedings, and its three manifestations could have been genuinely interesting and even (gasp!) scary in their dynamic interrelations, but despite their seeming high profile, the script never thinks to treat the supposed ghosts/monsters/whatevs as anything but a throwaway red herring.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

michel gondry's BE KIND REWIND (2008)

i've been struggling with this one all weekend, being repeatedly asked about it and not quite being able to recommend it. Be Kind Rewind is a thoroughly pleasant movie, and hard not to smile at, but it'd be dishonest to call it good; Eternal Sunshine (and to a lesser extent the affecting but minor Science of Sleep) suggested Gondry as a storyteller talented beyond the confines of his quirk, but Be Kind Rewind determinedly contradicts, clumsily throwing sentimental whimsy at a cute premise and calling it a movie. the "sweded" movies starring Mos Def and Jack Black (a good duo, even if Black's schtick is finally wearing thin) are a lot of fun, and the film would have perhaps been better off accepting itself as a simple frame for their VHS shenanigans, but its gentle, well-intentioned questioning of art's (and history's) relationship to its audience takes over halfway through and bogs down what should have been a light entertainment with ideas, however innoucuous and sweet, beyond its modest capabilities.

i've been struggling with this one all weekend, being repeatedly asked about it and not quite being able to recommend it. Be Kind Rewind is a thoroughly pleasant movie, and hard not to smile at, but it'd be dishonest to call it good; Eternal Sunshine (and to a lesser extent the affecting but minor Science of Sleep) suggested Gondry as a storyteller talented beyond the confines of his quirk, but Be Kind Rewind determinedly contradicts, clumsily throwing sentimental whimsy at a cute premise and calling it a movie. the "sweded" movies starring Mos Def and Jack Black (a good duo, even if Black's schtick is finally wearing thin) are a lot of fun, and the film would have perhaps been better off accepting itself as a simple frame for their VHS shenanigans, but its gentle, well-intentioned questioning of art's (and history's) relationship to its audience takes over halfway through and bogs down what should have been a light entertainment with ideas, however innoucuous and sweet, beyond its modest capabilities.

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Saturday, February 09, 2008

vincent paronnaud & marjane satrapi's PERSEPOLIS (2007)

“In this life you’ll meet a lot of jerks. If they hurt you, tell yourself that it’s their own stupidity that makes them act that way. That will keep you from responding to their meanness. There’s nothing worse in this world than bitterness and revenge.”

“In this life you’ll meet a lot of jerks. If they hurt you, tell yourself that it’s their own stupidity that makes them act that way. That will keep you from responding to their meanness. There’s nothing worse in this world than bitterness and revenge.”first published in France in 2001, Marjane Satrapi’s black and white graphic autobiography Persepolis has enjoyed a significant degree of crossover success throughout the world, and for good reason: her introspective, emotionally loaded memoir represents the best facets of what we talk about when we talk about comics as art (paving the way for similarly outstanding works like Craig Thompson’s Blankets and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home) while telling a lively, universal, and occasionally devastating tale of childhood.

what makes the book so significant, however, is its backdrop. Satrapi’s early adolescence was spent in the shadow of the Iranian Revolution, which in 1979 saw the country transition violently from monarchy to theocratic republic, and Persepolis is most valuable in its accessible survey of the complexities and contradictions of pre- and post-Revolution Iran, all seen through the eyes of a little girl to whom Islamic law and nationalistic fervor mean nothing compared to the safety and happiness of those she loves. it’s not the story of a hero, but of an observer forced to learn, endure, and eventually escape to the relative sanity of the outside world.

still, Satrapi remains reverent to her roots and her nation, and the result is illuminating for Westerners seeking insight and context into the generally alien Islamic world: we are shown, as we should be shown every day, that within these sad, prideful national constructs are millions of people with the same problems and aspirations as anyone else in the world.

now Persepolis has found its way to an even larger audience by way of Satrapi & Vincent Parranoud’s Oscar-nominated animated feature, a combined abridgement of Persepolis and its 2004 sequel. the film follows Satrapi’s tiny pen-and-ink doppelganger through these formative years, as she dreams of being the last prophet before the revolution shifts her country’s well-being from bad (the Shah) to worse (Khomeni) to worst (the bloody, protracted Iran-Iraq War.) eventually her parents decide to send her to school in Vienna, where her horizons are finally allowed full latitude, but her pride in and love for the people of her shattered nation eventually bring her back…for a time.

Satrapi & Parranoud’s film is gorgeously animated, refitting the book’s rough-around-the-edges illustrations with a slicker but no less evocative cartoony style, brought to life in an unobtrusive blend of hand-drawn animation and computer compositing. but where Persepolis’ whimsy and gravity jump to the screen with equal facility, its heart sadly seems lost in translation. given that Satrapi’s saga isn’t as well-suited to cinematic story structure as it would seem, she’d have done well to disregard it altogether by allowing the first half more breathing room; it is, after all, the sociopolitical context (and Marjane’s precocious reactions to it) that drives Persepolis, and glossing over strong material lamentably dulls its impact. so, too, does Satrapi seem to assume the emotional resonance automatically carries over from page to screen, and the overall result is a partially hollow adaptation, lacking the full spectrum of warmth and sharp insight that make the source material so essential.

still, it’s hard not to recommend Persepolis. it’s pleasing and instructive, and as worthy elucidation of ideas and cultural history as you’re likely to see onscreen this season. but behind its superb visuals there’s a gripping, intimate human drama insufficiently tapped, so unless you’re really in the mood for popcorn your twelve dollars may be better spent at the book store than the box office.

(from the KNOXVILLE VOICE)

woody allen's CASSANDRA'S DREAM (2007)

it’s not easy being a Woody Allen fan. American cinema’s comic laureate has released a film practically every year since his 1969 debut Take The Money And Run, running the gamut between ribald gag-a-minute comedies and philosophically smothering chamber dramas as he carved out a body of work as curiously personal as it is significant. a handful of his films are among the all-time greats, and at least fifteen more aspire closely to greatness. but several others are just okay. and, to be very honest, an increasing number are damned dreadful. such is the curse of productivity.

it’s not easy being a Woody Allen fan. American cinema’s comic laureate has released a film practically every year since his 1969 debut Take The Money And Run, running the gamut between ribald gag-a-minute comedies and philosophically smothering chamber dramas as he carved out a body of work as curiously personal as it is significant. a handful of his films are among the all-time greats, and at least fifteen more aspire closely to greatness. but several others are just okay. and, to be very honest, an increasing number are damned dreadful. such is the curse of productivity.in 2005, however, Woody’s diminishing batting average was unexpectedly bolstered with the home run that was Match Point, a sharp, wicked tale of luck and murder set across the pond from his beloved New York City. besides being better than anything he’d made in at least half a decade, the film exhibited an encouraging restlessness in Allen’s craft, and at the age of seventy he proved he could still surprise his audience. was it his newest muse, Scarlett Johansson, or perhaps the United Kingdom itself, that so inspired him? his subsequent film, the middling Scoop, suggests not. so perhaps it was the straightfaced, low-key crime drama?

the answer, for better or worse, lies in Cassandra’s Dream, Match Point’s opposing bookend in his British trilogy. the film centers around Ian and Terry Blaine (Ewan McGregor and Colin Farrell), two lower middle class South Londoners with a propensity for living beyond their means: Terry chases spurts of good and bad luck to the dog tracks and high-stakes private poker games, while Ian daydreams of hotel investments and woos a beautiful actress with optimistic lies. as the chasm between means and aspirations expands, their successful Uncle Howard (Tom Wilkinson) blows into town with a dark proposition dressed up in language of generosity and family loyalty: a former associate is preparing to testify regarding unsavory business practices, and must be dealt with. capital D, capital W.

and thus the brothers Blaine are faced with a tough decision, and its consequences reverberate through the rest of the film: one brother tries to cope with guilt and fear, the other with their absence. superficially, Cassandra’s Dream echoes Match Point in its form: Allen again plays the film straight (he stays behind the camera, for one) and pulls off another impressive exercise is style and restraint. in content, however, the film is much closer to 1989’s Crimes & Misdemeanors, an earlier masterpiece dealing with the spiritual implications of murder gone unpunished.

sadly, Cassandra’s Dream lives up to neither. one of the main problems is the characters: as with Match Point, he has little trouble bridging the cultural divide, but here the added problem of social class proves trickier; Allen has his heart set on nuance and realism, but his scripting undoes him, taking little care to disguise what amounts to a poored-down version of his typical milieu. this becomes a serious problem as the film progresses, as the story and its psychology hinge entirely on Ian and Terry’s desperation, but time and time again their plight rings untrue, and so the events in motion around them carry the weight of contrivance.

even worse, the film’s conscious echoes of Crimes & Misdemeanors end up working against it as well, if only because C&M is a much more definitive piece of work; Allen borrows against his own ideas a little too enthusiastically, and though Terry’s plight adds another dimension to the struggle, his weakness seems somehow affected and dramatically insufficient. Ian’s arc does push the story into pulpier territory than C&M dared tread, and the film is engaging throughout, but it’s hard to ignore the soft hum of a coasting filmmaker, especially by the film’s abrupt, unsatisfying finale, a small wonder of boring irony.

ah, but then, I’m only rough on Woody because I love him so. (this isn’t an uncommon affliction among Allen apologists.) Cassandra’s Dream is still in many regards an impressive 38th feature film by a onetime standup comedian, branching out confidently as it does into unfamiliar territory that proves just slightly beyond its grasp. and as much as Match Point has probably spoiled fans into hoping he’s got another ace up his sleeve, for the moment it’ll suffice to be quietly thankful that he’s still making stabs at greatness amidst a slow decline of recycled whimsy. see you next year, Woody.

(from the KNOXVILLE VOICE)

re:

drama,

england,

noir,

published,

woody allen

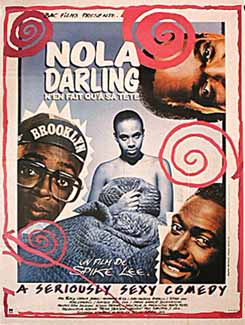

spike lee's SHE'S GOTTA HAVE IT (1986)

finally available on DVD, She’s Gotta Have It is as assured a first feature as exists in independent film, and of notably modest origins to boot; Lee strides with confidence, even arrogance, through a witty, intimate portrait of libertine Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns), a small constellation of friends and a trio of suitors: the genial Jamie (Tommy Hicks), the vain Greer Childs (John Canada Terrell) and Lee’s own fast-talking alter-ego Mars Blackmon. unapologetic in her embrace of her own sexuality, Nola juggles the three men much as they’ve surely juggled other women, giving way to a funny, sexy, surprisingly perceptive survey of sexual politics circa the mid-1980s.

finally available on DVD, She’s Gotta Have It is as assured a first feature as exists in independent film, and of notably modest origins to boot; Lee strides with confidence, even arrogance, through a witty, intimate portrait of libertine Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns), a small constellation of friends and a trio of suitors: the genial Jamie (Tommy Hicks), the vain Greer Childs (John Canada Terrell) and Lee’s own fast-talking alter-ego Mars Blackmon. unapologetic in her embrace of her own sexuality, Nola juggles the three men much as they’ve surely juggled other women, giving way to a funny, sexy, surprisingly perceptive survey of sexual politics circa the mid-1980s.in fact, Spike’s subsequent (and only intermittently productive) preoccupation with racial issues is nowhere to be found in She’s Gotta Have It, which makes the film all the more significant within his body of work; not only does he focus all of his energy on Nola’s personal plight (as well as a startlingly accomplished comedic performance as Mars) but in forgetting to address race directly he actually manages his first forward push for African American cinema, making a universally smart, accessible film about human sexuality in which all the characters just happen to be black.

sadly, years of waiting for a lovingly prepared DVD (I can finally toss out my battered VHS) are for naught: MGM’s release is the very definition of barebones, showcasing an indie hallmark without so much as a trailer to accompany it. where’s the Lee commentary? (if he can write a whole book about the film’s production, he can surely jaw about it for ninety minutes.) furthermore, where’s Mars Blackmon’s “It’s Gotta Be The Shoes” commercials with Michael Jordan? a missed opportunity for too-long overlooked film, but a joy to have available nonetheless.

(abridged from the KNOXVILLE VOICE)

re:

black cinema,

homosexuality,

lee,

NYC,

published,

sexuality

p.t. anderson's THERE WILL BE BLOOD (2007)

there's a lot i could probably say right now about There Will Be Blood - about Anderson's shocking maturation as a filmmaker, about the film's brave, sure disposal of story in favor of blistering character study, about Daniel Day-Lewis' virtuosic (there is no other word) embrace of a hate-driven capitalist metaphor walking the earth as a man. but as immediately apparent as it is that Day-Lewis' Daniel Plainview is one of cinema's grandest monsters, he's also gorgeously inscrutable, and i'm resigned and eager to revisit the film in search of greater understanding, content for now that a spiritual foulness of such magnitude is beyond my grasp.

there's a lot i could probably say right now about There Will Be Blood - about Anderson's shocking maturation as a filmmaker, about the film's brave, sure disposal of story in favor of blistering character study, about Daniel Day-Lewis' virtuosic (there is no other word) embrace of a hate-driven capitalist metaphor walking the earth as a man. but as immediately apparent as it is that Day-Lewis' Daniel Plainview is one of cinema's grandest monsters, he's also gorgeously inscrutable, and i'm resigned and eager to revisit the film in search of greater understanding, content for now that a spiritual foulness of such magnitude is beyond my grasp.

matt reeves' CLOVERFIELD (2008)

every bit as novel and clever as its pokerfaced advertising campaign, and terrific besides, Cloverfield has finally gifted American film its own Godzilla. we've had our big baddies, sure, and stolen our fair share on top of that, but it's the psychology that makes the monster; just as Godzilla sprang from the anxieties of a post-nuclear Japan, the Cloverfield monster plows through New York City with a weight far beyond its mass. the conceit of the "post-9/11 monster movie" is a reasonably obvious one, of course, nearly as obvious as the likely wrongheadedness of such a project. yet here JJ Abrams and his team bravely sell the destruction of New York with a deft intimacy, stimulating the tension with love and loss while building from their gimmick rather than around it. it's an exercise in both populist postmodernism and pure genre (the nearly-toppled building setpiece is particularly brilliant), made all the more terrifying by the all-too-real idea of an evil we have to face without any hope of understanding.

every bit as novel and clever as its pokerfaced advertising campaign, and terrific besides, Cloverfield has finally gifted American film its own Godzilla. we've had our big baddies, sure, and stolen our fair share on top of that, but it's the psychology that makes the monster; just as Godzilla sprang from the anxieties of a post-nuclear Japan, the Cloverfield monster plows through New York City with a weight far beyond its mass. the conceit of the "post-9/11 monster movie" is a reasonably obvious one, of course, nearly as obvious as the likely wrongheadedness of such a project. yet here JJ Abrams and his team bravely sell the destruction of New York with a deft intimacy, stimulating the tension with love and loss while building from their gimmick rather than around it. it's an exercise in both populist postmodernism and pure genre (the nearly-toppled building setpiece is particularly brilliant), made all the more terrifying by the all-too-real idea of an evil we have to face without any hope of understanding.

woody allen's CRIMES AND MISDEMEANORS (1989)

in a lot of ways Crimes And Misdemeanors, one of my very favorites of Allen's films, seems to finally achieve what he'd been striving for to that point in his career; as obvious as the angle between them is (and as much as Woody might disagree) the dueling planes of his art intersect perfectly, satisfying his high-minded dramatic urges on a grand scale even as his own role serves up a tasteful, minor comedic story that allows itself to resonate within the narrative thanks simply to the fact that there's no pressure to carry it. his best pictures to this point had been dramedies like Manhattan and Hannah, but here he finally uses human relationships as a means rather than an end, and the result is not only one of American film's most penetrating looks at religious faith but also the emergence of Allen as a full-blown cynic, presenting a somehow darker variation on Crime And Punishment that's shocking in its fearless amorality. on rewatching, the script stands out, as it ought to: a lot of the film's power comes from the work of a master at his most focused and disciplined (if for no other reasons than to meet the steep demands of the comedic/dramatic dichotomy) and the core of that work here is a remarkable flair for scene transitions.

in a lot of ways Crimes And Misdemeanors, one of my very favorites of Allen's films, seems to finally achieve what he'd been striving for to that point in his career; as obvious as the angle between them is (and as much as Woody might disagree) the dueling planes of his art intersect perfectly, satisfying his high-minded dramatic urges on a grand scale even as his own role serves up a tasteful, minor comedic story that allows itself to resonate within the narrative thanks simply to the fact that there's no pressure to carry it. his best pictures to this point had been dramedies like Manhattan and Hannah, but here he finally uses human relationships as a means rather than an end, and the result is not only one of American film's most penetrating looks at religious faith but also the emergence of Allen as a full-blown cynic, presenting a somehow darker variation on Crime And Punishment that's shocking in its fearless amorality. on rewatching, the script stands out, as it ought to: a lot of the film's power comes from the work of a master at his most focused and disciplined (if for no other reasons than to meet the steep demands of the comedic/dramatic dichotomy) and the core of that work here is a remarkable flair for scene transitions.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)